To create memorable moments is to step out of your daily routine. And this is exactly what I did in the Spring of 2023, when for two weeks, I stepped away from my work and family, and joined a group of strangers in Guadalajara, Mexico, for a deep exploration of architecture and the built environment. Strangers with whom I had one thing in common: an interest in architecture not as an aesthetic expression of a visual artist, but as a complex body, both functional and poetic, which allows humans to live healthy and meaningful lives. Architecture as an extension and a completion of the human body. This bunch of strangers, many turned friends since, were a mix of architects, historians, lighting designers, cognitive scientists, psychologists, and neurologists. For two weeks, we all learned from each other’s fields of study. We discussed, debated and experimented with designs which truly put the human being as the conception seed of a built space. Moving Boundaries continued to grow since, becoming a strong medium both online and throughout the world. In the Spring of 2025, I had another amazing opportunity to reconnect with old friends and make new ones during a retreat in Amares and Porto, in Portugal, where we continued sharing knowledge and inspiration on similar themes, and where personally meeting the great architect Álvaro Siza was a highlight and a true moment of inspiration.

And because I found it difficult to put into words these quite elevated intellectual and emotional experiences, I invited Tatiana Berger, the founder of the Moving Boundaries course and movement, to join me for a conversation, and reveal the true and noble intentions of the movement she created. On a higher level, this is a discussion relevant to our work as acousticians, as sensory designers, and ultimately it is a profound exercise in reframing our goals as building designers, whether we are architects, lighting designers, acoustic, landscape or so many other flavors of designers.

Tatiana Berger is an architect, urban designer, educator and consultant, who holds a B.A. in Architecture from the University of California Berkeley, and a Master’s Degree in Architecture from Princeton University. Ms. Berger has over 35 years of international experience in professional practice and education. She sits on the ANFA (Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture) Advisory Council and is a consultant for human-centered design. She has practiced in the United States, Portugal, Spain, Russia and Austria, and collaborated with some of the most renowned architecture and engineering firms in the world, including the Portuguese Pritzker-Prize winning architect Álvaro Siza, Richard Meier in New York, and Baumschlager Eberle in Austria.

Her numerous built works, community plans, and collaborations were published in international periodicals and presented in exhibitions in Madrid, Lisbon, New York, Moscow, Venice and other cities. Ms. Berger taught at the New School of Architecture & Design in San Diego, where she developed the Neuroscience for Architecture Program, at the Boston Architectural College, at Roger Williams University, and she co-founded the Compostela Institute, an academy for the study of architecture and landscape architecture in Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Ms. Berger is Director and Professor of Architecture and Design at Moving Boundaries Collaborative.

Ioana Pieleanu

Ioana Pieleanu

Moving Boundaries, as I understood and experienced it in Mexico and later on in Portugal, is a potpourri of many subjects. It is about architecture, poetry and lighting, neuroscience and cognitive sciences, among other topics. All of this, building around an architect who distinguished themselves through work that flourished in this creative realm of art and science. In Guadalajara, for instance, this was Luis Barrágan.

To start with, I am curious: what was your journey, from graduating as a young architect focused on visual design and 2D drawings and details, to creating the Moving Boundaries program, which approaches architectural design as an incredibly rich and multidimensional process. What does it take to evolve from an activity that is primarily a visual expression, to a multi sensorial expression that is ultimately at the basis of wellbeing, the way you present it in Moving Boundaries?

Tatiana Berger

Tatiana Berger

When we look back on twentieth-century architectural theory and design education, we see that much of it was remarkably reductive in the parameters with which design was concerned. You are right, that the focus was often on architecture as visual expression, on the creation of objects, without much regard for the human experience. This formalist and reductive approach continues in some schools of design to this day. My educational journey was quite different from the beginning. In my first year at UC Berkeley, I started studying biology and genetics. I joined the department of architecture a year later, but even then, I felt the need to create an interdisciplinary curriculum for myself, which included courses in cultural studies, sociology, literature, and anthropology in addition to architecture and construction.

My advisor in the department of architecture was a bit confused at first. We had many conversations about the role of design in society, and it was here that I first began to realize how important human sciences and the humanities were in the education of a designer. So no, my education was never limited to 2D drawings and visual design, but I had to be creative in engaging with multiple university departments. I had to piece together a non-traditional interdisciplinary curriculum.

In graduate school, at Princeton University, I was given plenty of time to develop ideas about architecture as a dynamic, multisensorial and embodied activity, one that places human experience at the very center. The realization that architects and urban designers could actually impact health and wellbeing came later, when I joined the office of Portuguese architect, Álvaro Siza Vieira. At the same time, I was fortunate to learn from several mentors and friends, such as Kenneth Frampton, Juhani Pallasmaa, Harry Mallgrave, and William Curtis, some of whom later became faculty members at Moving Boundaries.

It is striking that human culture, traditions, context and history were rarely addressed in certain schools of design. Any understanding of the body and mind, perception and emotion in space were remarkably absent. While working with Siza, I recognized the huge gap between mostly formalist and reductive education, so common in the academy, and the multidimensional and empathetic design practice, that he had been developing now for decades. And so, by gaining that critical edge through my new experience in Europe, in the office of a master architect, I realized the importance of creating a grassroots movement to affect change. I set out to recast design education, to try to bring it closer, once again, to the understanding of the human experience of space.

Ioana

And because you had such an in-depth glimpse into Álvaro Siza’s day-to-day work, how did you see him approach and use the human and community resources in his work?

Tatiana

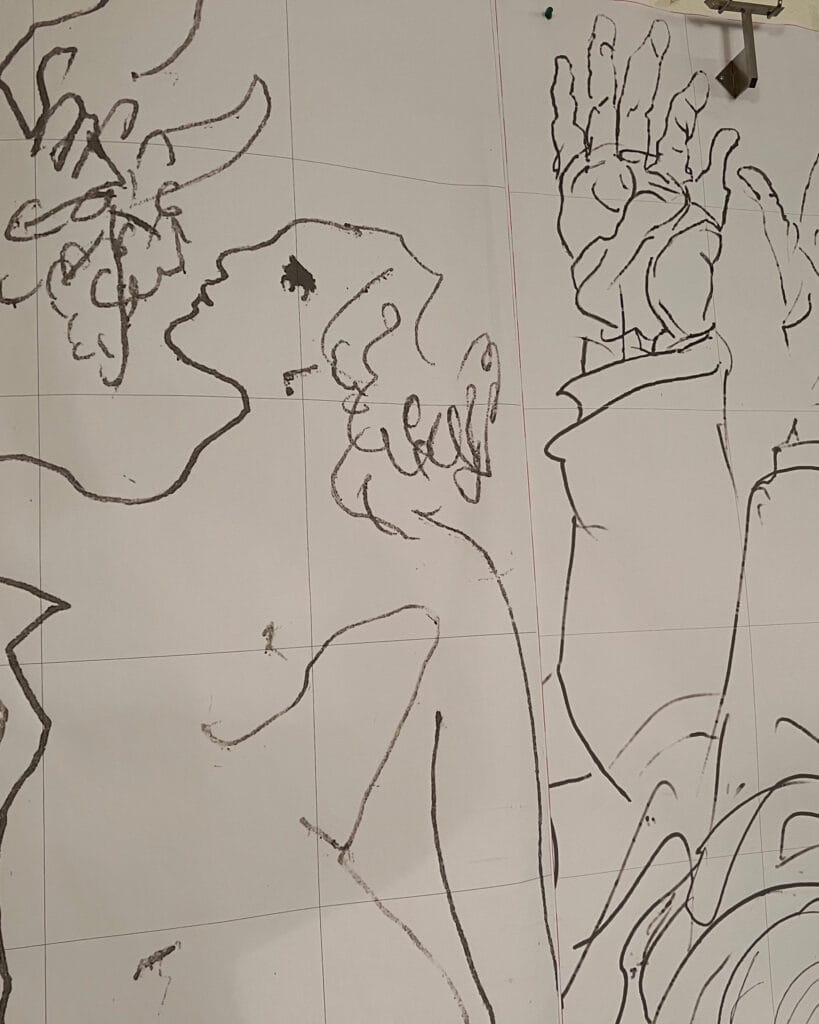

That expressed itself on multiple layers. First, he draws people in parallel with spaces, constantly, obsessively; he’s never without his sketchbook. And there are thousands of sketchbooks stored in museums and archives around the world. It was a great pleasure for me to witness him filling his sketchbooks with personal expressions, not only of architecture, but also poetry and literature. People often appear on the pages, sometimes overlaid with building plans or perspectives. Siza is always imagining the movement of people through space. And then out of that, an architecture magically emerges. In Alvaro Siza’s work, I witnessed the importance of expressing with the body and through empathy and perception.

Second, there were interactions with the designers in the office and with craftspeople and builders, who would visit often, to help us create the furniture, or fixtures, or lighting. Siza listened carefully, and it was really through beautiful conversations with multiple figures, through those dialogues, that the architecture then emerged.

The human connection and conversation were always at the center, and the force behind the development of the design. And finally, community participation is always at the heart of his practice. Particularly the housing projects in Germany, in Portugal, and many other places, included dialogues with local communities in the planning stages and after completion. Siza’s work is intimate and sensitive at many scales, whether it is a chair, building, or an urban neighborhood.

Ioana

Creation as an expression of an artist, a craftsperson, an architect, inspired by the human being and designed for the human being. In sound, and I am thinking now in music, in particular, there is this concept —which I embrace —that you need the listener to complete the musical creation. Half of the artistic work belongs to the interpreter on stage (composer/ performer) and half to the interpreter in the audience (listener). The composition is not fulfilled until it reaches the listener, he or she being an integral part of the musical act. And there is a constant push and pull, a tension and release in the artistic act, both in the score itself, but also in its communication to the listener. When you developed Moving Boundaries, I sense that you thought of both the architect and the future building occupant.

So, in practicing and in teaching architecture, how do you think of that building occupant? Who are you creating for? Am I correct to assume that at the center of those sketches and creative process was not only the human as source of inspiration but the human as the ultimate recipient of that product and creative process?

Tatiana

Of course, yes. I learned during those years spent in Siza’s office, that the architect must be, first of all, an empathetic and a cultured individual. That being a great architect does not only depend on our technical skill and not even on the ability to solve problems. Of course, all of that is very important, but first and foremost it is the empathetic understanding and being able to connect with the needs of people (individuals and communities both) that matters most. And this is something that Siza always did beautifully. He has a great love for people and therefore an understanding of their needs in a particular space. That is absolutely central.

Ioana

Let’s fast forward to Moving Boundaries. What is in this name?

Tatiana

The first word in the title of our initiative, “moving” speaks to a flow in-between different phases and states, something that is always changing. We are always innovating, and we allow ideas and the curriculum to evolve, often dramatically, based on the place where the program is immersed. Moving Boundaries is a hybrid: it is an educational program, a research institute, an artistic and humanist initiative, and a community, all at the same time. “Boundaries” refer, of course, to geographic and cultural boundaries and also to boundaries between disciplines. Artificial boundaries are placed between disciplines for one reason or another. Those reasons can be political, in academia or in practice. People sometimes restrict themselves artificially in silos and this is very unfortunate, as it prevents development and conversation. Think for instance of the realms of architecture, interior design, landscape architecture and even urban design. The design of our environments needs to be seen as a whole, as a gestalt where one way of thinking impacts another, and where everyone can recognize the importance of collaboration for the common good. Our initiative is interdisciplinary and international, and so the idea of moving boundaries seems quite fitting for the name.

Ioana

What are the Moving Boundaries’ mission and goals?

Tatiana

One of the main goals is to create and support a community of interdisciplinary professionals to enhance research efforts, nurture new collaborations, and to bring a more humanist approach to design practice and education. Many of the participants make lifelong friends at these programs. And, at the same time, we want to help this community build their own grassroots movement, both on a global scale and in their own region. We have participants coming from many different countries: there are often 35 or 40 countries represented. We encourage them to take these seeds, which they gather during the course, back to their home and to affect change on many levels with the support of their new community.

We believe that encounters of scientists and design professionals produce an exciting new frontier of human knowledge, and they lead to new understanding of the roles and responsibilities of the designer. Discoveries in the neuro and cognitive science fields from the last three decades have been truly groundbreaking, and they illustrate the impact of different spaces on human health and wellbeing. We see the potential to improve and even to save lives, when designers learn how to apply this knowledge in their projects. In its larger aspirations, MB aims to serve as a platform for collaboration between educators and scientists, health experts and clinicians, practitioners and students of architecture, as well as with institutions of design, research and learning.

And ultimately, we aim to affect change in design education and practice, by putting the human dimension and the focus on health at the center of the architect’s mission. We have the luxury of operating a bit like an experimental laboratory, because we are fully independent from any universities or institutions, which allows us to create and innovate a new type of design curriculum, that we believe can lead to really meaningful change.

Ioana

Let’s talk a little more about the faculty. There is a high ratio of faculty to the number of students. There are many faculty involved, all people at the top of their fields. How do you choose them and how do you establish a curriculum to serve all these ambitious goals we have talked about so far?

Tatiana

We select the faculty based on their accomplishments in their own discipline, and as you said, they are all at the top of their fields, and also based on their potential to contribute to a meaningful dialogue with other disciplines. The curriculum relies on a successful collaboration, and all kinds of new insights that come out of this, in preparation for and during the course. The lectures and workshops at the program are always exploring knowledge at the interface of health and human sciences, architecture, design and planning.

We ask our professors to prepare what we call “dialogical lectures”, where an architect is paired with a scientist while the program is being prepared. They do not just lecture on a topic of their expertise, something that they’ve done a billion times, and which we know they can do brilliantly. The goal is for each expert to push herself outside of comfortable boundaries, to reach a whole new level of discovery and innovation. Additionally, our curriculum integrates learning through a combination of masterclasses, talks, workshops, panel discussions and tours, and it is this immersive experience in a local culture, and dialogues with place and people, that allow us to reach many of the goals that you asked about.

Ioana

What you are describing makes me think very much about our work in building acoustics. Working on a different aspect of the same design. There is the architect, the lighting designer, the acoustic designer, the mechanical engineer, the structural engineer, etc., and together you create a whole. My day-to-day work is to have these dialogues. I cannot operate in a vacuum because, for me, the vacuum does not translate into anything. If we don’t have brick and mortar, if we do not have an architect with a building concept, there is no building acoustics to talk about. We are always in this interesting dialogue, which can be uncomfortable many times, until we make something great happen. When you, as an expert, express yourself in a monologue, it’s a certain kind of expertise. But when you have to collaborate and to share, when you are part of a communal brain that creates something, I think that is an expertise elevated to the power of n, and that is really the place, the level that I like to work at, and which I find both most fulfilling and most challenging.

Tatiana

Absolutely. Our world is becoming so complex that expertise in only one subject is no longer beneficial. True progress and innovation will depend on the strength and strategic vision of interdisciplinary collaborations, and we try to teach those soft skills in our programs, to nurture them in our developing research institute. Curiosity, critical thinking and empathy will lead the way.

Design education has been stagnating for several decades. For a long time, academic design programs took meaning and inspiration from post-structuralist theory, film theory, literary theory, which really could not be any further from humanistic concerns. And we can see the results of that abstract and formalist approach in the buildings of those years, mainly in the 1980’s and 90’s. Media-driven, spectacular, and ultimately inhuman architecture has become more extreme in the past two or three decades.

So, the paradigm change for us, the challenge, is quite simply to bring the focus in design back to an understanding of human biology, perception and modes of behavior in relation to space and built form. We need to understand how humans experience space in real time, where users complete and enrich the narrative of the designer. And then, a larger goal is to connect with the health professions, to better understand the effect that spaces have on human health and wellbeing, including the long-term effects of multiple factors in the built environment.

Ioana

Other institutions, for example The Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA), started pursuing this complex approach to architecture some 20 years ago, focusing on similar core values as you describe, putting an accent on perception and study of perception and cognition, on understanding how the brain responds to certain architectural situations. And maybe Moving Boundaries took all of that a step further in that you introduced a cultural context, a hands-on context, by traveling and exploring architecture “live” rather than through literature. Other programs that contribute to this shifting, maybe in a different way, are LEED and WELL, as well as other programs designed with goals of sustainability and human wellbeing. Do you think those programs help promote these values? Because, ultimately, the destination is the same: a building that’s better for the environment, for human beings, and a building that addresses all the senses and dimensions we encompass.

Tatiana

All of these groups are doing valuable things. As we follow our mission and goals at MB, it is important for us to include multiple disciplines and perspectives, and we do not see the mind and body as separate entities. We allow ourselves to evolve because of the freedom and independence of MB as an organizational structure: it is flexible, nimble, experimental, grassroots and bottom-up, and it is able to adapt to different circumstances. We know that many different human sciences (as opposed to just neuroscience) and, in particular, environmental psychology and sociology, act as very natural bridges between sciences and architecture. Science alone is not enough.

We believe in the importance of grounding all of our actions and ideas in a deep understanding of culture, place, people, histories and traditions, with a more humanistic and ethical approach. And this is why our initiative operates like a ‘traveling university’, for programs held twice a year, and as a research institute and community, in-between the on-site immersive courses. We are nomadic because in each new program, in each new place, we have so much to learn from the local wisdom. We train students to study places and people closely, and to integrate their research in each phase of the design process. We also believe that the humanities have to be present at all levels of design education and practice, instead of focusing mainly on science and technology.

Ioana

Thank you, this is much food for thought for all of us in the AEC world. I would like to shift focus a little now, and talk about acoustics, about experiencing a building with our sense of hearing. I want to ask you what your relationship with a building is, through the sense of hearing? When you step into a building, are you aware of sound? Do you think about it? Does sound, or the singing of a building, let’s say, contribute to your aesthetic and functional experience when you step into that building?

Tatiana

Sound is central to our perception of space. Some of the most memorable architecture, and I loved how you said architecture that sings, is where the form of the building has actually been informed by its acoustic atmosphere. A great example would be the Bagsvaerd Church by Jorn Utzon, which is just outside Copenhagen.

Photo Credit: Rob Deutscher

If you study drawings of this building, the section especially, you will see that the form of the building has been created to deliver specific acoustical effects. And so when I stepped into this building, the visual experience was not primary. Instead, I actually heard the singing of this building. This offered new levels of understanding of space, and a range of meanings that are quite rare.

Another building, where sound shapes space and vice versa, is the MIT Chapel in Cambridge, in a simpler way, but equally beautiful. Each space has its own distinct sound, or absence of it.

Photo Credit: Naquib Hossain

Perception is always multisensory, so yes, acoustics contribute to our aesthetic experience, in collaboration with all other senses. I think the design process can be much richer if we allow ourselves to think about sound and acoustics to help us develop the form.

Ioana

While we are talking about architectural form and sound, and their aesthetic expressions informing each other, we must recognize that there are also a large number of buildings where all we aim to do, on a very functional level, is to neutralize the building’s acoustic response. Since most spaces are designed for human interactions, having as primary goal good speech intelligibility, designers promote interior finishes that enhance speech intelligibility, while eliminating the building’s unique acoustical character, which comes from reverberation, and a certain pattern of sound reflections. It’s a functional and an aesthetic question, both, that we have to ask ourselves as designers (architect and acoustician together): when and how much of the building sound are we to enhance or to eliminate, and why.

Tatiana

Certainly, we need to create a comfortable environment for human speech and interactions, but we also have to learn much more about how different acoustic environments make us feel. We need to think about designing not just visual environments as we’ve all been trained, but about, let’s call them sensory environments. We should understand the effects of spaces and acoustics on our mood, emotions, and on our health over time. We know that uncomfortable and noisy environments can make us sick, while quiet, calming spaces can slow our heart rate, improve mood and maybe even reduce the risk of disease over time.

The acoustics of a space may add to the building’s beauty, and we can even imagine the sound of a space as invisible form. Knowledge from the human sciences, many new discoveries and new methods of gathering data can help us with some of these questions. As you say, often it is about eliminating sound for the benefit of speech intelligibility, but sometimes it is useful to also hear the building sing like an instrument. The beauty is really in the relationship between the body and space, and in how the space speaks to us. A silent space also speaks, more through emotional energy than through sound.

The paradigm change we have been discussing is really based on ethics, and this has not been tackled by design institutions often enough. We need to introduce ethics in our design curricula from the very beginning. The idea is that once we understand what an enormous effect our sensory environments have on our health and wellbeing, then our entire approach needs to change. We are now aware of this responsibility. If we are ethical practitioners and educators, we simply cannot continue to practice in the same way.

Ioana

I am so honored to have had the opportunity to attend Moving Boundaries and to have had this discussion with you, Tatiana. I truly believe architecture will grow with us, the more we understand about designing for the senses, for human beings and for entire communities. Thank you!

Photographs included throughout article courtesy of Moving Boundaries | Mexico City & Guadalajara, Mexico

About the Author

Ioana Pieleanu – As Creative Director, Ioana leads Acentech’s marketing and business development efforts across multiple industries. A former architectural acoustics consultant with over two decades of experience, Ioana also curates content for the Lab @ Acentech, our interactive online portal. The lab provides listening experiences via web3DL – immersive 3DListening® technology that allows users to hear the acoustics of different space conditions and designs using standard headphones.